|

| Professors Trevor Kincaid (L) and Thomas C. Frye original photo 1961, by Roy Scully. from the archives of the Saltwater People Historical Society. |

‘Instead of studying all about a sea cucumber, someone studies its blood supply’, said Prof. Trevor Kincaid, zoologist. ‘There is a shift in emphasis. Biological science has become an adjunct of physics and chemistry.'

Dr. T. C. Frye, Kincaid's partner in the original enterprise, remembers how the pair divided studies so that one took all marine animals and the other, all marine plants. They also divided administration matters, Kincaid planning and scheduling expeditions, and Frye keeping the accounts.

Kincaid, 88, was here at the inception of the Friday Harbor project. Dr. Frye, 91, who still keeps office hours in the botany department at the university, joined the faculty after the site had been chosen. He was in time to initiate the first season's work.

The two men alternated as director for a number of summers, to permit each to engage in other fieldwork.

The staff is recruited from the departments of botany, meteorology and climatology, microbiology, oceanography, zoology, and the College of Fisheries.

Speaking of the laboratories' long incubation period, Kincaid said that when he arrived in Seattle as a student in 1894, a member of the Young Naturalists Society, Philip P. Randolph, took him on a weekend expedition to dredge for specimens in Puget Sound. They used a two-handled windlass rigged to a small tugboat, the MOTH, which was fueled with driftwood.

For two summers Columbia University maintained a temporary marine laboratory on a wharf at Port Townsend. The presence of this New York contingent stimulated the desire of the U of WA faculty to have similar facilities.

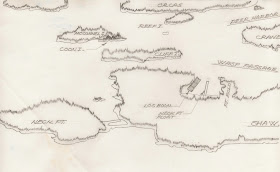

Kincaid who meanwhile had attained teaching status, and N. I. Gardner, a graduate student in biology went to Friday Harbor about 1899 on a collecting trip and were entranced by what they found.

When the Board of Regents of the university was won over to the idea of a marine laboratory, I opposed going as far away as the San Juans. Kincaid and H. R. Foster, botany professor, were instructed to find a site nearer Seattle, such as the old camping place at Rocky Bay or the abandoned Columbia University site, which Port Townsend had offered.

‘I had it in my head that either move was merely temporizing to satisfy the authorities and that we would make no mistake at Friday Harbor where opportunities for marine studies were exceptional’, Kincaid said.

In the spring of 1904, the university announced opening of the station with an enrollment fee of $10 and $3 for lab charges. The entire cost of fees, board, laundry, and incidentals, for a season was no more than $45.

Classes began 23 June in a cottage rented from Edward G. Warbass, on the south side of the harbor. The 19 students and two faculty members lived in tents. They built their own kitchen, dining, and lab tables.

|

| University students and their tents on "campus" at the Puget Sound Marine Biological Station Friday Harbor, WA., undated original photos from the archives of the S. P. H. S.© |

At other times, parties walked along the coast of San Juan or crossed the island by lumber wagon to tramp in mud over their shoe tops, gathering mollusks and seaweed at Kanaka Bay and other shallow bays. It was Dr. Frye’s first experience at the seashore—he was from Illinois—and he has not forgotten the day the dredge brought up a fighting eight-ft shark.

The next summer, classes moved into the unoccupied Pacific American Fisheries cannery, using the ‘China house’ for kitchen and mess hall and the main building for laboratory. Tents were scattered behind the establishment.

These facilities were available until cannery operations were resumed in 1905. Boat transportation in this period was furnished by a shrimp-dredger *.

Kincaid in this interval, had established a cooperative plan of studies, attracting professors and their students from Oregon, Iowa, Kansas, and the normal school at Bellingham, now Western Washington College of Education.

Washington State College opened a marine-studies camp at Olga, on Orcas Island, and in 1909, the two schools arranged for students to spend three weeks there and three weeks in the old facilities at Friday Hbr. The university temporarily reoccupied the Warbass cottage, then owned by Andrew Newhall.

The joint arrangement was impractical, as tent floors and kitchen equipment were cumbersome to transfer from one island to another.

The State Legislature had appropriated $6,000 for a lab building and the university tried to obtain federal land on which to erect it. To keep the establishment at Friday Hbr, Newhall donated a four-acre site with 1,000 yards of waterfront, adjoining the old cottage.

The lab, standing several stories high, still can be seen, overhanging the water. It stood partly on cement piers, with a landing float anchored in front.

Again students slept in tents scattered up the slope. Toward the end there were 61 tents.

‘We needed to expand, Kincaid said, ‘and Mr. Newhall asked a high price for additional land. A highway had been run across the property, taking out a large part of it, making an escarpment on the upper side of the road and furnishing a perpetual source of dust. It was becoming very uncomfortable.

‘We decided to try again to obtain a portion of the idle military reservation on the north shore of Friday Hbr. An act of Congress was required to get it for us.

|

| U of W Marine Labs, Friday Harbor, WA. Undated photos from the archives of the S. P. H. S.© top photo by Ferd Brady. |

The land was secured in 1921, and construction of new buildings was started two years later. The government retains ownership of the property in emergencies; in wartime, this was a Coast Guard station.

The year Dr. Thompson became director, the oceanography department got funds for the laboratories from the Rockefeller Foundation.

‘Dr. Thompson was a chemist who specialized in sea water, a dynamic person who was bound to make the institution go places,’ said Kincaid. ‘Under him, the type of studies expanded and changed.’

The work at Friday Hbr has broadened to such an extent that the labs have attracted foreign experts in their special marine fields and the station has been the scene of international conferences. So much has been accomplished in studies of worldwide impact that the humble beginning of the place has been lost.

Today’s work runs to parasitology, behavior of certain sea creatures, endocrinology, the physiology of reproduction, the electric, chemical, and mechanical aspects of a crustacean’s neuromuscular inhibition, the distribution of an enzyme, and the mechanism of uptake of radioactive phosphate from seawater, by an embryo sea urchin.

The research now is all highly refined and far-reaching in results compared to light-hearted students of nature who roamed the islands with buckets in those early years."

Above text by journalist/historian/author Lucile McDonald (1898-1992)

Seattle Times, February 1961.

McDonald authored or co-authored 28 books. From 1932, except for 3 years absence, she lived in Washington State. She and later, her son, donated her papers to the University of Washington Library.

.jpg)