Thomas M. Henry of Pasadena, seaman first class aboard the cruiser MINNEAPOLIS, leaned over the table in an East Madison Street tavern and said, amiably: "O.K. British. Shell out, we win."

Four seamen from His Majesty's light cruiser, the ORION, dug ruefully into their pockets. They came up with five-pound notes and sundry shillings and tuppences.

"To a great crew," said Seaman First Class Henry. "Had all my dough on it."

The MINNEAPOLIS in the fifty-first Battenberg Cup race had won again.

So had Thomas M. Henry and sundry other inveterate gamblers of the American fleet. It has been twenty-two years since a British whaleboat succeeded in defeating a crew of the US Navy.

But an hour later, on the porch of the Seattle Yacht Club, Capt. H.R.G. Kinahan, commander of the ORION, which had challenged for a cup a countryman of his put up in the interests of British-American goodwill in 1906, said:

"We are particularly thankful for the opportunity the Battenberg Cup race presents...the opportunity for ships crews and officers getting together.

"If we could have a bit more of that sort of thing these days, everything would be much more peaceful."

The Battenberg Cup race needs explantation, to a Seattle audience which had never seen, and seldom heard of it before. The cup was first given the American Navy to Prince Louis of Battenberg, commanding the British Second Cruiser Squadron, in 1906. It was received aboard the MAINE, then flagship of the fleet; and it has been contested for innumerable times. The American fleet competes for it annually. Whenever a British fighting ship comes within shouting distance of the American possessor of the cup, it may be challenged for again. This was one of those times. The ORION was visiting on a mission of goodwill. The goodwill still continues...but the MINNEAPOLIS continues to keep the cup.

The race was for a mile and a quarter, on the Leschi-to-Madison Park course that has been the scene of seventeen Times Cup Races. The MINNEAPOLIS won it hands down in 14 minutes, 35.4 seconds. The WEST VIRGINIA was second, the SALT LAKE CITY was third. The challenging ORION was a long-last fourth.

(Don't blame the ORION. British ships don't use whaleboats. They use "five hundredweight" cutters utterly unlike the US whaleboats, and the 3,000-pound boat the ten-man ORION crew rowed in the race had been borrowed from the cruiser ASTORIA. The men had only borrowed it for practice three days ago.)

The MINNEAPOLIS crew, coached, and coxed by M.C. Riddle, a lanky, stern-looking youth, took the lead at the start and never headed. The SALT LAKE CITY fought it out for the first half of the course with the WEST VIRGINIA, but the VIRGINIA pulled away.

The distance was so great between each crew at the finish that a Times photographer, 'shooting' from the top of the bathhouse at the foot of East Madison St with a telephoto lens, barely got the winner and the second-place boat on one negative; and then with plenty of time to reload he barely got the third and fourth place whaleboats in the second negative.

The crews were towed to the Seattle Yacht Club, where Rear Admiral R. E. Ingersoll, commanding Cruiser Division No. 6, 'restored' the trophy to coxswain Ridder and his crew with the acknowledgment:

"We wish to thank the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, the Seattle Yacht Club, the Coast Guard, and others; but most of all, Captain Kinahan and his ORION. Without them there could have been no race; the SALT LAKE CITY and the WEST VIRGINIA could not have challenged, at this time."

Then, turning to Captain Kinahan:

"But you did have us worried when we heard your boys were practicing so hard they were breaking their oars in training."

This, however, was far away from Seaman First Class Thomas M. Henry of Pasadena. When last seen he was setting up bottles of beer for the house and admitting, calmly;

"That MINNEAPOLIS crew...Hell, mister, they can't be beaten!"

Text by Ken Binns. For the Seattle Times. July 1939.

Time Line of other Marine History Articles (156) only listed here.

▼

29 September 2019

23 September 2019

❖ MERMAID on the STARBOARD BOW ❖

|

| Mrs. P. A. Brant admiring the mermaid art painted on the bow of a beached reefnet boat, perhaps ashore for the winter season. The boats belonging to this reefnet gear had been anchored to fish for salmon off Point Roberts, Whatcom County, WA. Photo dated 26 October 1952. The Lummi, Saanich, and Cowichan peoples made nets of willow bark to fish here for hundreds of years until pushed aside by non-native fishermen working for Alaska Packers Association in 1895. Click image to enlarge. from the collection of the Saltwater People Historical Society© For E.H. |

MERMAID

"A fabled creature, half-woman and half fish, which appears in the folklore of all lands, and which is firmly believed in by sailors at least until the 19th C. The mermaid legend has been ascribed by some to observations by early explorers of the manatee, a small cetacean found in Caribbean waters, which has the curious habit of rearing itself on end partway out of the water. The probability is, however, that the legend is as old as that of the siren, a mythological creature, half woman and half bird, who was believed to haunt certain rocky isles in the Mediterranean and, by her sweet singing, lure mariners to destruction on the rocks."

Source; Johanna Carver Colcord. Sea Language Comes Ashore. Cornell Maritime Press, New York. 1945.

16 September 2019

❖ A Bout with Surf ❖

"North Shore, Orcas Island. How different are the islands! How like the different countries even the different shores of the same island. This northeast shore of Orcas is a strange land, steep, high, with dark, forbidding beaches. Along the part that is the waterline of Mount Constitution, the trees seem to lie flat, they look as if one bank of them grew out of those below. The kelp beds are close against the bank which means deep water very close to shore.

As we near Buckhorn Lodge, a sleek, new mahogany boat upholstered in blue leather comes flashing out to meet us. Ten seconds ago it was at its moorings, now it is alongside us and Mr. Payson from Tacoma, the owner of these 115 leashed horses, offers us a tow to wherever we are going. We accept. The wind failed some time ago. We've been rowing a long way. A tow for five minutes behind this boat will take us nearer to our night's camp-spot than we could walk with our arms in two or three hours.

The Harndens live somewhere along this north shore. We have an invitation to camp on their beach. It is past six o'clock, time to camp.

People all along here are picnicking down on their beaches, fishing, or sitting on porches, talking dreamily. Houses sit on bluffs, hidden, secret. Or they cluster together low on the beach, friendly, gregarious––but which house is the Harndens'––they who used to live on Sucia Island? 'About a mile down the shore,' a girl shouts out to us. We have let our horses go back too soon.

Slowly, we ease along this shore, looking for a comfortable beach. Underwater boulders left here by the glaciers are strewn over the low tidelands. We'd go aground, or a-rock, on one of those and never get off! On and on.

This is low land, now––the isthmus at the head of East Sound. Just a mile down there is the village. We'll go over there tomorrow and spend the day talking to some of the most interesting old-timers in all the islands.

Sand dollars! My stars, look at them all over the bottom of this bay! Black, standing up on edge, they look even stranger than when we find them on beaches, white and dead, mere skeletons, their star-shaped centers cut out with holes like the doors of an old kitchen safe.

This tall white house with the luscious garden and the flowers, all with such a ship-shape look––this must be the Harndens. I'll just go ashore to say we're camping on their beach tonight––and they are not home.

We camped anyway, not far away, on a shallow beach below the old salt marshes which are now fertile fields. It had the feel of prairie there––a new feel in the islands. We got a sudden sense of homesickness for the prairies of Oklahoma which we both have known. Home! How many places turn out to be home. How many places are wonderful and dear for some sudden sharp likeness to a little spot on which you stood to watch a meadowlark on a fence post, maybe.

But that night another north wind came up. We had awakened to a sunrise clear and pure, the old ball rolling up over Lummi Island and shining straight across to us, still comfortably abed. Then all at once, without the slightest warning, there was the wind and in two minutes flat, surf rolling in over this flat beach.

'We'll be aground in 10 minutes,' Farrer shouted as he ran down the beach, throwing off pajamas and grabbing on garments as he ran. I follow only one button behind him. At the water's edge, we were fully dressed, but we shouldn't have been, for in two more minutes we were fully wet pushing off the boat. But we managed to load it before it could quite come ashore.

And so, away again, breakfastless, tickled at our first brush with surf in our lives.

We'd row on around Point Doughty to Orkila, the YMCA boys' camp, we said. They had invited us. We could dry out there and ––maybe!––they might ask us to breakfast.

But if it had been any later than five o'clock in the morning, we'd never have made it. It took us nearly three hours to row those few miles, for the wind wasn't going our way and, for once, we didn't propose to go its way. Finally, we rounded the point, slide down the bay to Orkila.

And, sure enough, a man came down the beach to meet us. It was Mr. Emory, director of the Queen Anne 'Y' in Seattle. 'You'll have breakfast with us?' he said and we said you bet and in no time at all, boys had secured our boat in the lesser surf on this beach. Boys had built a fire in the big dining room and a day at Orkila had begun.

We met 125 boys and 30 staff members.

We went down the beach to see Mr. Kimple's and his two partners' Beach Haven resort, where Dr. Turner of the University's new medical college caught five salmon the first time he ever fished in our waters, met Mrs. Fleming, wife of Seattle's superintendent of schools, sitting on a log knitting, had some cookies made by Mrs. Kimple. That's all for today! See you tomorrow. June."

If you have been following along with this Log there are many more excerpts from the newspaper articles by June Burn entitled One Hundred Days in the San Juans. She had a contract with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1946. In the 1980s editors with the Longhouse Printcrafters in Friday Harbor, published them in a book format, under the same title. Now a collector's item.

|

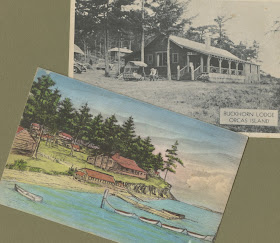

| BUCKHORN LODGE The view from the water as mariners, June and Farrar were rowing west to Harnden's beach. From the archives of the Saltwater People Log© |

As we near Buckhorn Lodge, a sleek, new mahogany boat upholstered in blue leather comes flashing out to meet us. Ten seconds ago it was at its moorings, now it is alongside us and Mr. Payson from Tacoma, the owner of these 115 leashed horses, offers us a tow to wherever we are going. We accept. The wind failed some time ago. We've been rowing a long way. A tow for five minutes behind this boat will take us nearer to our night's camp-spot than we could walk with our arms in two or three hours.

The Harndens live somewhere along this north shore. We have an invitation to camp on their beach. It is past six o'clock, time to camp.

People all along here are picnicking down on their beaches, fishing, or sitting on porches, talking dreamily. Houses sit on bluffs, hidden, secret. Or they cluster together low on the beach, friendly, gregarious––but which house is the Harndens'––they who used to live on Sucia Island? 'About a mile down the shore,' a girl shouts out to us. We have let our horses go back too soon.

Slowly, we ease along this shore, looking for a comfortable beach. Underwater boulders left here by the glaciers are strewn over the low tidelands. We'd go aground, or a-rock, on one of those and never get off! On and on.

This is low land, now––the isthmus at the head of East Sound. Just a mile down there is the village. We'll go over there tomorrow and spend the day talking to some of the most interesting old-timers in all the islands.

Sand dollars! My stars, look at them all over the bottom of this bay! Black, standing up on edge, they look even stranger than when we find them on beaches, white and dead, mere skeletons, their star-shaped centers cut out with holes like the doors of an old kitchen safe.

This tall white house with the luscious garden and the flowers, all with such a ship-shape look––this must be the Harndens. I'll just go ashore to say we're camping on their beach tonight––and they are not home.

We camped anyway, not far away, on a shallow beach below the old salt marshes which are now fertile fields. It had the feel of prairie there––a new feel in the islands. We got a sudden sense of homesickness for the prairies of Oklahoma which we both have known. Home! How many places turn out to be home. How many places are wonderful and dear for some sudden sharp likeness to a little spot on which you stood to watch a meadowlark on a fence post, maybe.

But that night another north wind came up. We had awakened to a sunrise clear and pure, the old ball rolling up over Lummi Island and shining straight across to us, still comfortably abed. Then all at once, without the slightest warning, there was the wind and in two minutes flat, surf rolling in over this flat beach.

'We'll be aground in 10 minutes,' Farrer shouted as he ran down the beach, throwing off pajamas and grabbing on garments as he ran. I follow only one button behind him. At the water's edge, we were fully dressed, but we shouldn't have been, for in two more minutes we were fully wet pushing off the boat. But we managed to load it before it could quite come ashore.

And so, away again, breakfastless, tickled at our first brush with surf in our lives.

We'd row on around Point Doughty to Orkila, the YMCA boys' camp, we said. They had invited us. We could dry out there and ––maybe!––they might ask us to breakfast.

But if it had been any later than five o'clock in the morning, we'd never have made it. It took us nearly three hours to row those few miles, for the wind wasn't going our way and, for once, we didn't propose to go its way. Finally, we rounded the point, slide down the bay to Orkila.

And, sure enough, a man came down the beach to meet us. It was Mr. Emory, director of the Queen Anne 'Y' in Seattle. 'You'll have breakfast with us?' he said and we said you bet and in no time at all, boys had secured our boat in the lesser surf on this beach. Boys had built a fire in the big dining room and a day at Orkila had begun.

We met 125 boys and 30 staff members.

|

| Beach Haven Resort Click to enlarge. Original photos from the archives of the Saltwater People Historical Society© |

We went down the beach to see Mr. Kimple's and his two partners' Beach Haven resort, where Dr. Turner of the University's new medical college caught five salmon the first time he ever fished in our waters, met Mrs. Fleming, wife of Seattle's superintendent of schools, sitting on a log knitting, had some cookies made by Mrs. Kimple. That's all for today! See you tomorrow. June."

If you have been following along with this Log there are many more excerpts from the newspaper articles by June Burn entitled One Hundred Days in the San Juans. She had a contract with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1946. In the 1980s editors with the Longhouse Printcrafters in Friday Harbor, published them in a book format, under the same title. Now a collector's item.

12 September 2019

❖ FERRY QUINAULT Stands by for SILVER SALMON ❖

On one of the initial runs of the steel-electrics when returning from Sidney, BC to Friday Harbor, the ferry responded to a purse seiner's call for assistance. The fish boat whistled the ferry down, came alongside, and explained that a bad leak was filling up the fish hold, a flood of water seemed to be coming in from the stern-tube. The crew of eight were prepared to abandon the boat with the freeboard getting less and less and the water not draining to the bilge pump.

The seiner captain asked if the ferry could stand by for a while in the event their boat sank before they could plug the leak. He said in the meantime they would throw out the salmon to lighten the boat and try to get at the trouble. They had only the haul from one set aboard, probably 500 fish, so it wouldn't take long. The boat had two fish pews and they would pitch the salmon from the after end of the hold up to the open deck of the ferry. The ferry captain on the upper deck responded with, 'Have at it, we'll wait.'

The boat eased alongside the end of the ferry, made fast, and the salmon began to fly aboard. In fifteen minutes the after deck was covered with slithering 'silver' and the fishermen were able to pull out the floor section of the hold and get at the leak. They found the packing almost gone from around the bearing and by dint of fast but wet work, they tightened the gland enough for them to feel safe and yell up to the captain that they would be okay to poke along to Friday Harbor. The captain quickly pointed to the fish on the deck, then to the fish hold––about 200 had been tossed over. The seiner's captain pointed back and yelled, 'The fish are all yours for the help and the stand-by!' Then as the seiner drifted astern, the passengers shouted, 'Good fishing to you!'

Everybody on board went home with a salmon, compliments of the Washington State Ferries and the crew of the seiner GOLDEN LIGHT.

Mike Skalley; Seattle. An excerpt from Ferry Story, The Evergreen Fleet in Profile. Superior Publishing. 1983.

The seiner captain asked if the ferry could stand by for a while in the event their boat sank before they could plug the leak. He said in the meantime they would throw out the salmon to lighten the boat and try to get at the trouble. They had only the haul from one set aboard, probably 500 fish, so it wouldn't take long. The boat had two fish pews and they would pitch the salmon from the after end of the hold up to the open deck of the ferry. The ferry captain on the upper deck responded with, 'Have at it, we'll wait.'

The boat eased alongside the end of the ferry, made fast, and the salmon began to fly aboard. In fifteen minutes the after deck was covered with slithering 'silver' and the fishermen were able to pull out the floor section of the hold and get at the leak. They found the packing almost gone from around the bearing and by dint of fast but wet work, they tightened the gland enough for them to feel safe and yell up to the captain that they would be okay to poke along to Friday Harbor. The captain quickly pointed to the fish on the deck, then to the fish hold––about 200 had been tossed over. The seiner's captain pointed back and yelled, 'The fish are all yours for the help and the stand-by!' Then as the seiner drifted astern, the passengers shouted, 'Good fishing to you!'

Everybody on board went home with a salmon, compliments of the Washington State Ferries and the crew of the seiner GOLDEN LIGHT.

Mike Skalley; Seattle. An excerpt from Ferry Story, The Evergreen Fleet in Profile. Superior Publishing. 1983.

09 September 2019

❖ FULL-RIGGED SHIP HENRY VILLARD ❖ 1882-1929

|

HENRY VILLARD 95688 219.2' x 39.8' x 24.1' G.t. 1,552 / N.t. 1,452 Launched 17 May 1882 at Arthur Sewall & Co, Bath, Maine. Low-res scan courtesy of the State Library Victoria, AU. |

The Henry Villard was named for the first president of North Pacific Railway and was built to carry material used in constructing the road. She took out the first cargo of rails sent to the Columbia River and thereafter any of her voyages were to Portland, Seattle, or Tacoma with similar material. On two or three occasions she took case oil to the Orient and in 1901 made a voyage from Savannah, GA to Honolulu with phosphate rock. She was operated at intervals in the coastwise trade.

The Villard was a good carrier, generally loading 2250 tons of wheat, with no fast passages to her credit. On three occasions she took sugar from Hawaii to N.Y. and these passages were made in faster time, proportionally than her runs to or from coast ports, they being 97,100, and 107 days.

1907: Capt. Charles O. Anderson was master off Cape Flattery when a gale hit; he reported the barometer dropped to 28.65, the lowest reading he had ever taken in 20 years on the North Pacific.

1910: Operated under tow since this year by the Ocean Tug and Barge Co; they had retained much of the top hamper until taken over by Griffiths who found her laid up in the Oakland Creek.

1913: Capt. Griffiths purchased the Henry Villard at San Francisco and had her towed to Puget Sound by the steam schooner John C. Hooper, before her conversion to a barge for the ore trade between Granby mine at Anyox, B.C. and the Tacoma smelter. For over ten years she carried coal and ore on Puget Sound.

1929, Feb: After having been laid up at Winslow for a long time, she was purchased from James Griffiths & Sons by Nieder & Marcus, Seattle shipbreakers who had her towed to Richmond Beach, saturated the hull with gasoline and then burned to recover the copper and iron used in her construction. The funeral pyre of the Henry was shared by the legendary Sound speedster, Flyer, sold in her old age as the Washington by Puget Sound Navigation Co to Nieder & Marcus.

Other associated crew:

Capt. James G. Baker was her first commander. He was formerly of the Sterling, who met death while the master of the Kenilworth. Capt. Baker made two voyages in the Henry Villard then succeeded by

Capt Fordyce B. Perkins. In command for eight years.

Capt. Frank W. Patten. (1854-1913) in command for three years. Son of Capt. Lincoln Patten.

Capt. Eben L. Murphy. Master in 1898.

Capt. Richard Quick, a native of Newfoundland who started sea life at age 12. He was in command for three years then went to Edward Sewell for 21 years.

Sources:

H.W. McCurdy's Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Gordon Newell, editor. 1965.

American Merchant Ships 1850-1900 by F.C. Matthews.