|

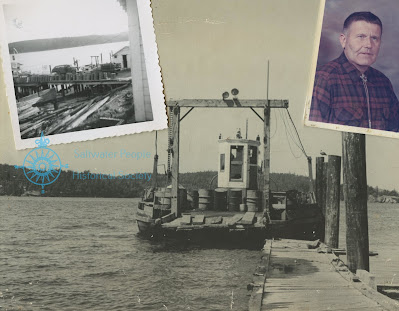

"Tib" Van Order Dodd (1895-1989) and Lew Dodd (1892-1960) Yellow Island residents Photo courtesy of their family. Click image to enlarge. |

(is what one Swede calls it)

Deer Harbor, WA.

December 1957

"Dear –––––––––––,

Well, the Islands are about rolled up in mothballs until Springtime, I guess, and from all appearances anyway–for there are extremely few boats to be seen nowadays; the Channels are deserted except for the mailboat and the ferry.

It is not really broad light in the morning until 7:30 and the sun (if any -and wherever seen) goes down behind the black San Juan Island hills at 4:15 PM. The whole Archipelago is slumbering and quiet in its usual winter hibernation so far as any comparison with June to October.

For the first time since last July, accompanying Jack Tusler in his boat, we went to Deer Harbor, most of whose sparse population isn't very much in evidence; for, those who can afford it have folded their summer tents, so to speak, and have migrated to the South––the road from Kirk's to the store, black in the gloomy wet and little traveled, and at Norton's dock a single troller leaning wearily against the float as if utterly tired out from the summer's fishing, the essence of ennui!

Blue smoke issues straight up from a few chimneys, and the forlorn old red cannery seems to stare vacantly upon the scene, which more than at any other time of year, resembles a small Port that once was and may never be again; deserted, forlorn, useless, abandoned; hopeless! Hard by, across the inlet, at the bridge, a forlorn sawmill no longer sings a tune, drift logs beachcombed, and red rust is King over all its metal machinery. The attitude which the whole hamlet has seemed to have acquired is one of extreme lassitude, and, perpetual waiting in a permeating forlorn hope that--well--"Something might occur someday; maybe." The place somehow manages to convey a very bleak empty and depressing picture as it sits on its sidehill, soggy, sodden, clammy, and damp--with its feet in the cold December sea. --Deer Harbor in winter! "The deserted village!"

We are always glad to return to our Island from such a brooding atmosphere, for upon clearing the vicinity the forlornness and the lifelessness leave one as if awakening from an unrealistic dream.

Back on our own Island, we are happy to pull the skiff up into its snug boathouse, shoulder the provisions, and climb the path to the bright, warm cabin where for so long as we have lived here we have been happy and content.

There is never a dull or uninteresting day at our Island home and no two days are alike: for there is always something, yesterday Tib and I watched two otters hauled out on our East end. It was a sight seldom seen by even those who do live in the country, and we may never see such an interesting performance as they went through with no idea in their heads that two human beings were observing through binoculars every move they made.

One reason that prompted me to drop you a line is because I wanted to (which is an excellent one, in my opinion!) Another reason is that I need Lloyd's advice:

Recently I saw an "ad" in December National Geographic of Zenith's new Transistor Transoceanic radio (8 bands) etc. price advertised as $250. Lloyd, what do you think of this radio and do you deal with them?

We are out here beyond television until they produce some kind of a battery set maybe––and even then if the programs don't get any better we wouldn't be interested. But, radio, a good one, yes, for it would give us worldwide contact everywhere, internationally––everywhere there are broadcasters. Ship to shore, aircraft, etc. How do these transistors stack up with the tube radios in performance? Do you think this new Zenith is a good buy at that price and could you buy one of them at any sort of a discount if you do not handle them?

I've been toying with this zenith idea to surprise Tib for Christmas. (I'm 65 now and may not last too long.) I can manage to pay for something that should give us whatever is to be had in worldwide radio for some time to come. But before I make any move at all I'd like your candid opinion about this machine. Just what your knowledge and experience can tell me. I will certainly appreciate it.

Tonight 8:00 PM we're having a hard westerly (about 40 mph) and the sea is noisy but the solid little cabin doesn't have a vibration in it, the kettle sings on the stove, the lamp is bright, and it a sweet, sweet home on an island in the San Juans far from the milling crowds and traffic, the fumes, and burning gasoline and the roar of trucks and trailers.

Our sojourn in Bellingham this summer, after so many years away from the modern clatter and clutter taught us both to appreciate and love even more our peace and quiet, sweet air, unchlorinated water, clear running tides; and natural surroundings, the seabirds calling and soaring in the clear, clean sky! We are so thankful and grateful for it all. It is a good life.

Our best wishes to you for a happy holiday season and we hope your year ahead will be a successful and contented one filled with whatever is GOOD and with whatever you most prefer."

Signed, Lew and Tib.

.jpg)

.png)