|

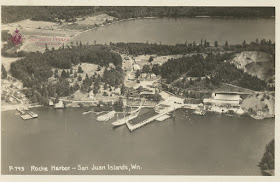

| Early photo of the Roche Harbor Lime Kilns postmarked 1909 San Juan Island, WA. Click to enlarge. Photo by J. A. McCormick. |

All that is needed is some strong backs to transport it to a plant and an oven that can reach nearly 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. At that temperature the rock becomes ‘calcined,’ it changes to a water-soluble residue. High-grade lime has been in demand for centuries in every industrial nation. So those hills around Garrison Bay were even more valuable than if they had been solid coal.

During the eleven years that the British Marines were quartered at English Camp on the northeast corner of San Juan Island, the chief occupation of the soldiers was not patrolling the area to resist invasions by the Yankees, or even to fight off occasional raids by the Haida tribesmen. Lt. Roche kept most of them busy quarrying the precious stone and stoking the fires under two primitive line kilns that they had installed nearby.

Hogsheads of the chemical were shipped by the Hudson's Bay Company to British possessions around the world.

When the English lost domain over the island in the decision handed down by the Emperor of Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm, the Crown lost access to a precious resource. Limestone in commercially worthwhile amounts is found only on San Juan Island in San Juan County.

The production of lime and its marketing, even though it was only a trickle from some quarries and kilns on Orcas and the San Juan Islands, attracted considerable interest from mining interests in the lower Sound communities. One of the most keenly-interested Yankees was a young attorney by the name of John Stafford McMillin who had been raised in a lime quarrying county in Illinois. He came to the Pacific Northwest in 1884, to practice law in Tacoma. When he discovered that there was a source of lime in the lands to the north, he bought into the fledgling Tacoma Lime Co and began to deal with buying and selling the commodity.

|

| ROCHE HARBOR, Inscribed "Largest Lime quarries west of the Mississippi River." |

Two Englishmen who had been prospecting for gold in California heard about the limestone quarry at the bay now named for the Commandant of the camp, Roche Harbor. In 1881 they bought the rights to the quarry and the two kilns and began to turn out lime.

McMillin, who had been able to find only a small amount of limestone near Orting for his new company got wind of the operation on San Juan Island. He began bargaining with the Scurr Brothers, Robert, and Richard, in 1884. By 1886, he had managed to buy the business from the Englishmen. He continued to operate the two army-installed kilns and created a new company, The Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Co.

Mining engineers calculated that the lode of limestone was three-quarters of a mile long and a quarter-mile wide. Not only was there enough rock for many decades of mining, but it was estimated at 98.32% pure carbonate of lime. What McMillin found was the most valuable supply of high-grade lime in the world.

In a short time, McMillin added three more kilns to the two original ones, which was called Battery #1. Then he built another, much larger plant comprising 8 kilns––Battery #2. These thirteen retorts consumed a prodigious amount of firewood––128 cords per day. The land attached to the Lime Works offered 4,000 acres of timber for the furnaces.

|

| The Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Co., The Company Town, San Juan Island, WA. Click image to enlarge. Undated photo. |

McMillin created his own little feudal domain. His company town offered the workers trim little houses, the store sold them supplies––both were paid for by scrip which was issued instead of money in pay envelopes. The workforce was made up of Orientals and single and married Caucasians. The single men were housed in a barracks. The Orientals were segregated into a cluster of houses over near the kilns referred to as 'Jap Town.' At its peak, there were 800 people who directly or indirectly were controlled by the Lime Baron.

While the injustices of the 'Company Town' system were prevalent in Roche Harbor, the Island community did have some needed facilities. There was a Company doctor, Victor Capron. There was a school for the children of the workers. The was also a Methodist Church.

Although the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Co community was a virtual fiefdom to itself, its influence was felt throughout the rest of the Island. When a regular newspaper came to the Island, it fell immediately under the influence of the magnate from Roche Harbor. McMillin became enormously wealthy and he was catered to by the Republican State administration and the business community.

The barrel factory had a phenomenal history of success in manufacturing. For centuries, barrels had been made by fashioning staves which were cut and beveled and bent into arcs to be put together with steel bands. It was a time-consuming and expensive operation. In 1897, McMillin invented a machine for carving hollowed-out barrel halves. A log the proper size for a barrel would be split in half and carved by a blade into a half-section of a barrel. When the two halves were finished, they were joined and sealed to make a

'staveless barrel. The shop was set up on the grounds and called the "Staveless Barrel Co.' With only 50 employees, the machines could turn out 4,000 barrels per day. This was more than enough to meet the demands of the lime works which boasted that they produced '1,500 barrels per day.' The surplus barrels were sold to shippers of other bulk products.

Whether old 'John S.' himself actually invented the wondrous barrel carving machine is not known. But the boss of the Lime Works had plenty of ingenuity when it came to financing. His fancy didos in the field of stock transfer and manipulation of funds almost earned him a jail sentence in 1906. The barrel company was involved.

John S. now had two hats: lime baron and barrel magnate. Wearing the manufacturer's hat, he asked for a contract to provide all the barrels for the lime works. With the quick change of headgear and he accepted the kind offer on behalf of the lime company (which had other stockholders, incidentally.)

In 1897, Mr. McMillin the inventor sold the new milling machine he had created to Mr. McMillin the Manufacturer––the price was $2,300. While he was in a dickering mode with the coopering McMillin, he sold the right to use the machine to fulfill the contract to supply the barrels to the lime miner. The price was $249,800 which was the exact amount of the stock issue on the Barrel Co. The stock was all owned, except for the one share to Keen, by Mr. McMillin. He bought the shares by signing a note for them.

Now we have a quarter-million-dollar factory, almost wholly owned by one man, with $200 in its treasury. John S. considered that somewhat untidy––money just lying around unused. So he billed the company $200 for his services in preparing the articles of incorporation. The company, with no demurral, paid the bill.

The minority stockholders in the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Co watched this juggling act with consternation. First of all, he became the majority holder by voting himself a raise in pay, even though the company was losing money. With the paychecks, he bought up most of the stock from frightened stockholders.

John S. now firmly held all of the controls over the mining, packaging, and distribution of the lime––except one––the transportation of it.

This called for the acquisition of another hat. It was not difficult for him to get since he was a wheel-horse in the Republican Party in Washington. The governor rewarded his contributions to the party coffers by giving him the job of State Railroad Commissioner.

The principal duty of this office was to ensure that all shippers were subject to the same rates. Mr. McMillin undertook the job and administered it firmly––with one minor exception ––he permitted the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Co to be granted a rate 2 1/2 cents per barrel lower than that of a competitor.

Eventually, the competitor, E.V. Cowell and several of the manhandled ex-stockholders forced the many-faceted panjandrum into a court of law. In front of a Federal Judge in Seattle, words like 'filcher, 'defrauder,' highbinder,' and 'venal bureaucrat' were bandied about.

It will come as no surprise to students of the age of rampant laissez-faire in business, a period called by President McKinley 'the Great Barbecue,' that all of the personages represented by John S. McMillin emerged as Simon-pure. With one exception. He did resign his job as Railroad Commissioner."

Jo Bailey-Cummings and Al Cummings. The Settler's Own Stories: San Juan: The Powder-Keg Island. Friday Harbor, WA. The Beach Combers, Inc. 1987.

Authors of Gunkholing in the San Juans.

No comments:

Post a Comment