"Geologists this summer (1959) combed the San Juan Islands in a study of limestone deposits, trying to determine how much of the mineral resource remains on the islands and how practical the deposits are for exploitation.

Long ago the white substance furnished the principal year-round payrolls in the islands and was one of the factors in their settlement. Quarrymen, kiln-tenders, and coopers comprised an important part of the population between 1870 and the end of the century.

Dr. W.R. Danner, a Seattle geologist on the U of British Columbia faculty, headed a crew sent out by the Division of Mines and Geology of the State Department of Conservation to make a comprehensive survey of the deposits in the past three months. He worked mostly in the San Juans and in Skagit County, while Dr. J.W. Mills of WA. State University, with a similar crew, carried on the search east of the Cascades.

Industries such as pulp manufacturing consume enormous quantities of limestone, now being imported into Washington because of lower production costs elsewhere.

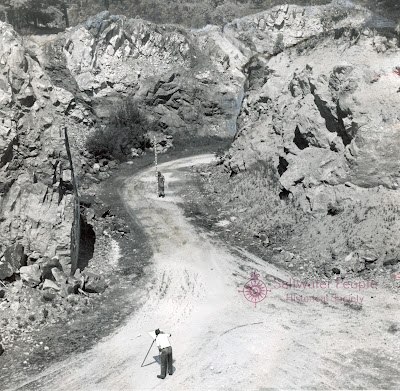

At present, only one operator, of the Everett Lime Co. deals in this commodity from the islands. He employs a crew to blast rock from the Westerman quarry at Eastsound, Orcas Island, break it into chunks called 'spalls', and load it on barges to be taken to pulp mills.

The market for Washington limestone has shrunk greatly. Only in cement manufacturing is it expanding. However, this outlet requires large and easily accessible deposits.

It was once supposed there was so much limestone in the San Juans that possession of tiny O'Neal Island alone was sufficient reason to justify the British-American boundary dispute of 1859.

Danner found this century-old idea amusing because, although limestone is visible on the surface of O'Neal, the island on close examination proved to have a negligible amount of the mineral.

'Islanders think lime is all over the archipelago,' Danner said. 'This is not true. It is found in small deposits; there are no great sheets of it. We want to discover what actually is here, what is left in the quarries, and what deposits have not been quarried.'

With his two assistants, Danner tracked down forgotten places such as limestone caves, crumbling towers that once were kilns, and prospect holes in picturesque fern-filled glens where early-day miners did not find enough mineral to justify quarrying.

'There are nine groups of quarries on San Juan Island and at least 14 groups on Orcas.' Danner said 'The Roche Harbor operation on San Juan, which ended several years ago after having been the largest on the Pacific Coast, had 12 quarries.'

The Roche Harbor plant was modern, compared with the ruins of earlier ones scattered in the islands. The towering old stone kilns, into which rock was dropped from the top and drawn out through oven doors at the bottom, have a medieval look about them.

Seven kilns can be seen on San Juan, ten on Orcas, two on Henry, and one in ruins on Crane, Danner says. The geologist found 21, including some which have almost disappeared.

Inaccessibility usually was the factor governing the closing of the old mines. A few were abandoned because of the height of overhanging cliffs, which threatened landslides. Another was shut down because of the death of a workman. Most became too costly to operate.

Danner had explored for lime in the islands in previous summers for private companies. This year he thoroughly examined San Juan, Orcas, Henry, Cliff, Crane, O'Neal, and Jones Islands for the state. He mapped old workings, took samples, and assembled all the lore he could extract from residents. Many of the lime properties have become residential sites.

The industry began on San Juan Island's west side, on the cliffs near Lime Kiln Lighthouse.

Augustus Hibbard, who became the island's first quarry operator in 1860, was a man who attracted trouble. Military authorities were annoyed with his men for keeping liquor in camp and selling it to soldiers and Indians. Hibbard's cook was stabbed to death by a cooper and Hibbard himself was killed by his partner, on June 17, 1868, in a quarrel over an Indian woman.

Hibbard died just before the completion of a new kiln. His heir, who journeyed from the East to take possession, died two years later. The federal census of 1870 indicated that the firm then employed 18 persons and in 12 months had produced 13,000 barrels of lime, worth $26,000.

Lime at that time was used mainly for mortar and as a soil 'sweetener' in agriculture. None had been discovered closer than California or Vancouver Island, so trade in Washington Territory appeared to offer good prospects.

George R. Shotter, a Canadian, opened the first quarry on Orcas about 1862, across Eastsound from the site where Clauson is mining today (1959.) The Shotter site, north of Rosario on Eastsound, is owned by the Crown Zellerbach Corp. Two ruined kilns on the beach are all that remains of the lime settlement of Port Langdon, which existed before there was a town of Eastsound.

Nova Langell, an old resident of the island, is a son of Ephraim Langell, a Nova Scotian who went to work at the quarry in 1871. He recalled that the company's oldest kiln has disappeared: the two standing on the shore are later ones.

In 1874, after American ownership of the San Juans was agreed through arbitration, the British quarry firm sold to Daniel McLachlan, an employee, and Robert Caines of Port Townsend, who later bought McLachlan's interest.

McLachlan went to the east side of San Juan Island and, with his brother, William, and Thomas H. Lee, a relative by marriage, in 1881, organized the Eureka Lime Kiln, on what became the property of Mrs. D.M. Salsbury.

Seven little quarries are scattered through the woods on Mrs. Salsbury's 250-acre tract and two kilns stand on the beach. Once a small community was on the spot, including a hotel, post office, saloon, and 20 families.

Eureka is one of the oldest quarries in the islands, older than the McLachlan-Lee enterprise. Probably it was opened by an Englishman named Roberts during the joint military occupation of San Juan by the British and Americans. Early in 1863, American squatters attempted to seize it from him through an illegal order of the Justice of the Peace. The controversy ended with Roberts's death by drowning before the year was out.

The Eureka property has not been operated since about 1890. Mrs. Salsbury converted two of the quarries into a Japanese grotto and a woodland chapel. Rock from one of the kilns was used for building her chimney and fireplace.

Danner found the forgotten quarry of the Chuckanut Lime Co. on the east side of Point Lawrence, Orcas Island. It was abandoned before 1910.

One of the most spectacular quarries, Danner said, is on the west side of Orcas Island, about 300' up in the cliffs, where the Orcas Lime Co plant for many years was operated by a woman, Mary Louise Dally. She and her husband, F.W.R. Dally, bought the original kiln on the President Cannel side of the island in 1900.

From 1914 until she died in 1928, Mrs. Dally had lime properties on San Juan and Henry Islands, including one with an ancient pot kiln, the most primitive type of oven to be seen in the archipelago.

Part of Danner's objective has been to learn the age of the limestone deposits in the islands, using tiny fossils of one-celled creatures that lived in shallow sea-bottom and were uplifted after the age of glaciers. On Orcas, he found limestone 350,000 years old.

The fossils, Danner said, are dependable clues to the age of any land where they exist. Through their presence, scientists have determined that the San Juan Mountains (now submerged, the islands are their peaks) ca. 200,000,000 years older than the Cascade Range.

The basic purpose of the summer work has been to learn whether suitable deposits of limestone are available to attract new industries.

Whereas kilns used to be of backyard proportions and a 200-barrel shipment was considered newsworthy in 1875, today's thinking has to be on a gigantic scale. If quarrying should reopen in the islands it will have to be undertaken by some large corporation financially able to overcome the physical obstacles and install an economical burning plant."

Words by historian/author Lucile McDonald and published by the Seattle Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment