A copper-plate engraving, from which one of the earliest navigation charts of Puget Sound was printed, was made available for exhibition in the proposed marine wing of the Museum of History and History.

The chart was dated November 1867. The copper plate itself is a relic of an art of years gone by.

The first copper-plate engraving of an American nautical chart was prepared in 1844 for a chart of New York Harbor. Such engravings were standard until after WW I, when they gave way to glass negative engraving and photolithography.

The Puget Sound engraving was turned over to the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society as a permanent loan from the Coast and Geodetic Survey.

It was presented 14 February 1957 by Rear Admiral H. Arnol Karo, director of the CGS, to Ralph Hitchcock, president of the PSMHS.

Robert Zener represented the Seattle Historical Society at the presentation in the office of Capt. Frank Johnson, Northwest supervisor of the Coast Survey.

Hitchcock said the copper plate will be kept in the Maritime Historical Society's custody until it can be put on display in the museum.

More than half of the $100,000 needed to construct the museum's marine wing has been pledged, Hitchcock said.

Source of text: The Seattle Times. 14 February 1957

About Us

- Saltwater People Historical Society

- San Juan Archipelago, Washington State, United States

- A society formed in 2009 for the purpose of collecting, preserving, celebrating, and disseminating the maritime history of the San Juan Islands and northern Puget Sound area. Check this log for tales from out-of-print publications as well as from members and friends. There are circa 750, often long entries, on a broad range of maritime topics; there are search aids at the bottom of the log. Please ask for permission to use any photo posted on this site. Thank you.

08 August 2025

HISTORIC ENGRAVED CHART of 1867

31 July 2025

Seafair Merry Making...... 1959

07 May 2025

A GLOW FROM VANCOUVER OVER THE SAN JUANS

02 May 2025

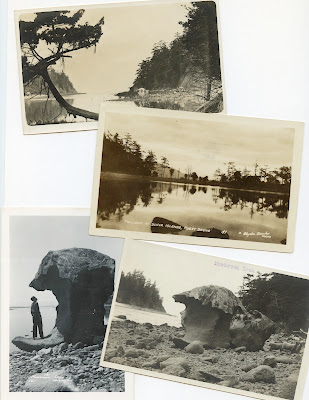

ENJOYING THE ARCHIPELAGO, with JUNE BURN, 1929.

"Just one week from today, I left Bellingham bound for the islands. Another too-perfect day for the return.

Dazzling sunshine and water ruffled prettily with a wind from over the sea and far away, pushing up the water into little humps that spill over on each as if in conscious play. There is a sense of awareness about the water, as if it responded voluntarily to the playful pushes and pulls of the wind, as if it ran sprawled upon the beaches just for fun.

The bluffs and beaches, coves, and villages of the island shine in the sun as if they had all just come home from the laundry. The Olympics behind us, Mount Baker softened by the thinnest veil of gray haze to the right of us, the white Cascades thrilling in front of us, Canada to the left and autumn-sweet islands around--if anybody thinks he can paint a picture to compare with that, let him try!

Down the channel again past Prevost, and Waldron, Deer Harbor, West Sound, Orcas, and Shaw, on over the three-hour run from Shaw to Belingham. I have my nose buried in my typewriter this heavenly day, racing to gather the harvest of my days in the islands before other days come swarming down upon me. We are in Bellingham Bay before I know it, the tip of Baker just disappearing over Chuckanut Mountain, across Eliza Island.

"There are more deer on Eliza Island than in the rest of the state of Washington." I hear one of the boatmen say. "They swarm around the cookhouses, so thick you can't get in. But take those same deer when they swim over to Lummi Island, and you can't get near them. They know they are protected here all right."

The neat white cement plant is the first building I can see as we draw in sight of Bellingham. Then, around the Point of Eliza, the smokes of Bellingham and the city itself pour down from all the hills into the bay. Are those the Selkirks over the horizon north-by-west? Shadowy through the yellowish-purple mist?

Five blackfish come spouting up the bay alongside the San Juan II. We leave them behind while we race over the wide harbor towards the city.

Like a wide, deep amphitheater is Bellingham swinging down and around the hills from south to north, the curve narrowing and deepening as we draw closer. South Bellingham in the sun is as colorful as a flower garden or as Heather Meadows in October. Tan and yellow and red and white against the brown and green of the hill. The Fairhaven Hotel is like a feudal castle nestled at the foot of the hill, while the new hotel in North Bellingham is like a young skyscraper. The smokes remind me of a New England factory town, while the beauty of the scene is like nothing but Puget Sound.

And Baker! You can't lose that mountain for long at a time! Here she is, her head and shoulders thrust up again over the hills! She is reminding me that Mr. Huntoon has promised to take me up that snowy radiance on snowshoes. I am glad to be hurrying back home! I had clean forgotten about that promise in the joy of the islands. What a world full of things to do in Puget Sound! And what a lot of friendly people willing to help you do them!

This is all of the island for a while--until next summer, maybe, though I make no promise! When the big winds come, I shall want to go down to see how the old eagle's nest rides the storm high in the branches of a dead fir tree. And I'd like to climb Constitution in the snow if there is to be snow this winter. I'd like to see how the spray freezes against a yellow bluff and the sun makes rainbows all down the bank of ice. I'd like to go stand on the end of Iceberg Point on Lopez Island and feel the wind beating against me from all over the Strait. You don't know your land at all if you know her only in summer! I think Puget Sound people, of all the people I have ever known, are winter-time folks, too!

See you tomorrow."

Published in the Bellingham Herald, evening of 5 November, 1929.

If you would like to view the vessel on which she jumped aboard, SAN JUAN II, it and more of her writings can be viewed on this post HERE.

30 April 2025

SUNDAY FOR SUCIA ISLAND ❖ ❖ 1894

|

Steamer BUCKEYE ca. 1892. |

"It was a happy party that boarded the steamer Buckeye for an excursion to the Sucia Islands, last Sunday.

There were small and large people, young and old people, men with their families, and boys with their sweethearts, all bent on having a good time. Well-filled lunch baskets were placed on board, with great care, which was amusing to behold. The trim little steamer left the wharf at a quarter to ten and anchored in McLaughlin's Bay a little after noon. The party landed near Mr. McLaughlin's home, and dinner was spread on the grass under some nice shade trees near the beach.

After dinner, several hours were spent roaming around the beach looking for curios, for which these islands have become famous. But the most "curious " thing found was the fact that the party could find nothing curious enough to be worth bringing home.

About half-past four, in the evening, the merry party gathered on board, the anchor weighed, and the steamer started for home. The evening was fine, the water smooth, and the trip home was a very pleasant one. A stop was made at Olga to land some passengers, and at Newhall, a stop of fifteen minutes was made, and a number of the passengers availed themselves of the opportunity to inspect the sawmill and the wonderful waterpower at this place.

The steamer arrived at Friday Harbor about nine o'clock, with all on board tired, but glad they had been at the party."San Juan Islander newspaper. 1894

The BUCKEYE was built at Seattle in 1890 and purchased three or four years later by Mr. Newhall to take the place of the little steamer Success. She was well-known to people in San Juan County for more than 18 years.

The BUCKEYE was last operated by the Olympic Towing Co when she was destroyed by fire at Stavis Bay, Hood Canal, WA., in 1930.

There is another post about this vessel suffering an accident the year following this party day at Sucia. Click HERE