|

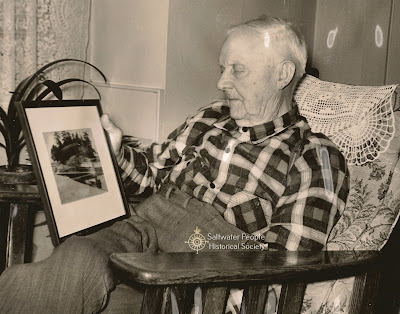

Captain Benjamin Joyce,

(1879-1971)

Life long mariner.

Photograph dated 1952.

Reports of an interview below

by Seattle's Lucile MacDonald.

Original photo from the archives of the

Saltwater People Historical Society© |

When the history writer, Lucile McDonald interviewed Capt. Ben Joyce for this essay in 1967, it had been 70 years since he had left home in Boston for a 14,300-mile voyage to St. Michael, Alaska, in a 122 ft halibut fishing boat.

Around Seattle, it would be hard to find another old salt who could match this cruise through two hemispheres in so small a craft.

Once upon a time, such voyages were fairly common, but most of the men who made them are long since gone. Captain Joyce began young, otherwise, he wouldn't be around to tell the tale.

"in 1897, l was an office boy in Boston when we heard news of the big Klondike gold strike. No one knew where the Klondike was, but every young man wanted to go. The story of the arrival of the steamship Portland in Seattle with a ton of gold on board didn't lose any in the telling. I was 17 and I got gold fever with the rest."

Joyce came from a line of sea captains and the tradition has been handed down to his sons, Capts. Emory and Ben Joyce Jr., and his grandson, Lieut. Comdr. Ben Joyce, in the Coast Guard, and Capt. Walter Hoopala, on a Foss tugboat in Vietnam.

At the time when the first young Ben got itchy feet, his father, Capt. Hanson B. Joyce was employed by the New England Fish Co. as the supervisor of fishermen. He had been going to West Coast halibut fishing each winter since 1892, and returning home for the summers because there were no facilities for shipping fish across the continent in warm weather.

In the spring of 1897, he was sent to Camden, M.J., to supervise construction of a new steam fishing boat, the NEW ENGLAND specially designed for catching halibut in the North Pacific. He was to see that it was the most efficient type for the work.

"She looked like a towboat with two masts, Capt. Ben explained. She never used the sails, but had them for emergencies.

"We wrote to father in Camden and told him I wanted to go to the gold rush. He said he'd do what he could to help me. He got me a job as a fireman on the NEW ENGLAND.

When the steamer was finished, my father high-tailed it overland in December to the West Coast, this time taking Mother, my two sisters, and a brother along. This gave me family connections to come to.

Young Ben went to Camden and joined the NEW ENGLAND to help take her to Boston.

"On the way, the chief engineer decided I'd never make a fireman in this world or the next. I was called on the carpet by the president of the company. He told me they'd have to make an ordinary seaman out of me. The crew already was filled when they found another fireman, so I went as deckman, meaning I was available to do anything. There were 18 of us on board.

We left Boston December 23 in bad weather and had to lie in at Woods Hole. From there to St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands was a nonstop run. We went in for coal and then left for Rio de Janeiro. We were sweeping the bunkers for fuel before we got in.

I was shoveling coal most of the time that trip; the sailors had to move it to where it was within reach of the firemen. We had coal all over that boat, in the fish holds, and stacked on the deck. It had to be that way because the stops were few and far between.

The weather was mostly fine all the way from Woods Hole to the Strait of Magellan.

|

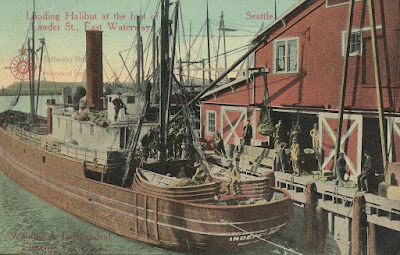

The INDEPENDANT

Landing halibut at Seattle, WA.

Postcard from the archives of the

Saltwater People Historical Society |

We coaled again at Montevideo. We never went into any of these cities because of the shipping congestion. The coal always was lightered out to us and we'd be on our way as quickly as we could.

We made the entrance of the Strait of Magellan at night and anchored until morning as there were no navigation lights in the passage. We'd gone into the Strait several hours when we saw a ship that looked to be on the beach. The captain thought she needed assistance, so we went over to her and found she was a Boston fishing schooner heading for Alaska.

She was full of fishermen with gold fever. She needed no help; she was waiting for the wind. We visited with them all that day –– it was Sunday–– and we were under way the next morning and out of the strait that night into a storm on the West Coast. By then, we'd got all the deck coal down into the hold, where the firemen could handle it, so we made out all right."

The next stops were at Talcahuano, Chile, and Callao, Peru, to refuel. Captain Joyce said by then he was "coal sick." He'd handled so much of it, along with the ash sent up in buckets and dumped overboard. Then on to San Francisco. The saving feature of the voyage was good food.

The New England arrived at Vancouver, B.C. in March, almost three months to a day, from the Boston departure. Joyce's father was there to meet him, having just finished the halibut fishing season. He took over command of the boat for the rest of the voyage.

"We were in Vancouver only about two days and then left for Seattle to pick up a tow of two river steamers for the Yukon. They were the ROCK ISLAND I and II."

We used the Inside Passage when we could and headed for Dutch Harbor, where we fueled again and father arranged to tow two more river steamers to St. Michael after we delivered the pair we had.

On the trip back from St. Michael, I had a new job – dishwasher and flunky. On the way north again, I was cook. I've done about everything."

The NEW ENGLAND began halibut fishing out of Vancouver in the fall. Capt. Joyce became captain of her in 1912 and left her in 1916 for bigger vessels.

Did he ever get to the gold rush?

"Yes, I had to get that out of my system. It took five weeks. I went to the Atlin, sluiced about a month on Pine Creek, and got a few specks of gold dust in the bottom of a pill bottle."

Joyce fished with his father on the NEW ENGLAND. She carried 12 dories and 24 fishermen They employed 350 hooks to a string and one day caught more than 200,000 pounds of halibut.

"At first we hoisted them aboard by the tails, but that was too slow for father. He put cargo nets in the dories and hoisted them out full in one lift.

The company allowed a fisherman 25 cents a fish when I began. Later we were getting 1.25 cents a pound. We worked sometimes from daylight to dark in the dories.

The NEW ENGLAND was sold for junk late in the 1930s. Captain Joyce retired in 1955, but he still carried his steamboat license, the oldest one on the Pacific Coast.

Above words by Lucile MacDonald, Historian/ Author. Published by the Seattle Times. 1967.

|

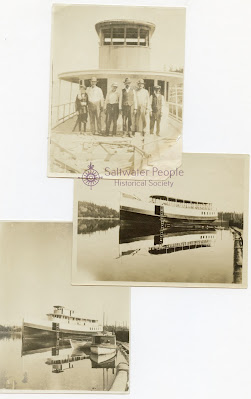

Capt. Benjamin Irving Joyce (L)

and son, Capt. Emery Joyce

Celebrating the 91st birthday

of Capt. Benjamin.

Original photo from the archives of

the Saltwater People Historical Society©

|

Many guests of honor had ridden with the captain on ships of the old Alaska Steamship Co passenger fleet. Joyce, who was born on an island off Maine, did most of his sailing out of Seattle. He received his masters papers in 1902 and was the oldest licensed master on the West Coast. The last time it was renewed, in 1965, the Coast Guard officer who signed it was Capt. Emory Joyce, one of three sons who became captains.

The celebration was at the home of Emory Joyce, now a Puget Sound pilot.

Text by Jay Wells, from the Seattle Times. Published February 1970.

.jpg)

%20.jpeg)