|

Asahel Curtis Photo courtesy of the WA. State Historical Society and Wooden Boat Magazine. |

Curtis was 13 when his family moved to Puget Sound but his father died within a few days of their arrival. The family was living in Port Orchard, Washington, when his older brother, Edward, moved to Seattle to join a commercial photographic business. When Edward dispatched Asahel to cover the Alaska Gold Rush of 1897, the younger brother had been working in the studio for two years.

Arriving at Skagway in early fall, Curtis headed up the trail to Lake Bennett and what he hoped would be a 500-mile sleigh ride in a crude drift boat down the Yukon River to the goldfields at Dawson. Starting too late, he spent the winter snowed-in at Summit Lake on White Pass. In the spring of 1898, low on provisions, he backtracked to Skagway, joined another party, and headed up again, this time via the rougher Chilkoot Pass. White Pass (also called Dead Horse Pass) was too steep for pack trains or dogsleds. It just devoured men. Curtis captured the hard realities of both places on 8" x 10" glass plates.

Edward Sheriff Curtis would later gain wide renown for his lavish series, the North American Indian. But in 1898, a heated dispute arose between the brothers after several of Asahel's Alaska images were published under Edward's name only. The brothers parted ways and never spoke again.

Asahel Curtis would continue his photography, slavishly recording an era of astonishing changes spanning the next four decades. From the agricultural boom of eastern Washington to the first ascent of many peaks in the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges, he moved easily throughout the Pacific Northwest on a multitude of projects. His detailed 1910 documentation of a Makah whale hunt off Neah Bay, for example, still defines this controversial practice.

He often encouraged other talented young photographers, sharing his studio with them. Imogen Cunningham, for example, often worked there. Curtis's early studio products included lantern slides, postcards, and "cabinet" prints, many hand-colored and framed in the popular "piecrust" style of the time.

An avid hiker and climber, Curtis became one of the area's earliest conservationists. He was one of the founders of the Mountaineers, a visionary group formed in 1906–and still very active today–to explore Northwest wilderness areas and collect the history of those places during a critical period.

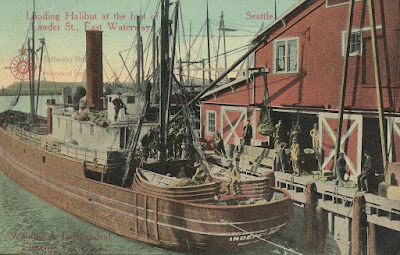

Curtis's prolific commercial work often took him out of Seattle to places of farming, fishing, logging, and manufacturing. His photos of native canoes, square riggers, riverboats, steamers, locomotives, and early automobiles followed 20th-century transportation as each mode was eclipsed by the next. His work appeared in periodicals ranging from Seattle newspapers to National Geographic.

In 1907, public interest in yacht racing exploded in Seattle, sparked by the dramatic Canadian-American match for the Alexandra Cup. Seattleites crowded the shoreline to witness some very close finishes. Large sums were wagered on the outcome. News and commercial photographers alike covered the races and found numerous markets for their photos. Vancouver, B.C., hosted a return match in 1908, but racing stopped abruptly in 1909 when the third challenge for the cup ended in a scandal that led to a bitter rift between the two cities.

While visiting Seattle in 1912, while en route to meetings in San Francisco, Sir Thomas Lipton heard about the dispute while spending considerable time being entertained by local yachtsmen and their families. Ever a supporter of the sport, Lipton offered a challenge cup for a race involving yachts in the R class of the new Universal Rule. The baronet's generous intervention would revive racing–and friendships–between these two cities.

The yachtsmen of both cities enthusiastically embraced the new format. The Alexandra Cup was put away and never awarded again. When the clubs met again in July of 1914, The Royal Vancouver Yacht Club took their new R–boat TURENGA south to face one of three Seattle boats, all purpose-built to defend the Lipton Cup. Together, they formed the first fleet of R–boats on the Pacific Coast.

Several Northwest marine photographers compiled larger catalogs of pleasure boating images than Asahel Curtis did–Webster & Stevens, Will E. Hudson, and Kenneth Ollar, come to mind. But Curtis was unique in capturing the feel of summer boating on Puget Sound with an artist's keen eye. At the same time, he covered the 1914 Lipton Cup races for Pacific Motor Boat magazine with a newspaperman's sense of history in the making."

Asahel Curtis worked in his studio until his death, in 1941. Sixty thousand of his images are held in trust by the Washington State Historical Society.

Thank you writer Scott Rohrer. and Wooden Boat magazine.

In August 1906, Asahel Curtis needed to explore above sea level; with his "Mazamas" mountaineering group he reached the summit of Mt. Baker over a route that others had pronounced impossible. He and six other climbers deposited their names in the iron box and left it a new resting place 400 feet further up from its previous position at 1 p.m., 9 August 1906, and were back to their main camp by 11 p.m.

The names of the climbers: F.H. Kiser, leader, of Portland; Asahel Curtis, of Seattle; C.M. Williams, of Seattle; L.S.Hildebrand, of Bellingham; C. E. Forsythe, of Castle Rock; and Martin Wahnlich, guide, of Bellingham.

At the head of the glacier that feeds Wells Creek, the party claims to have found a large vent in the mountain from which occasionally boiling water is gushed forth with a hissing sound.

The San Juan Islander. 1906.