|

Early Fairhaven, WA. Photographer P. L. Hegg From the archives of the S. P. H. S. © |

"My family brought me to Spokane in 1892 when I was very small; in 1904 we moved to Fairhaven, now South Bellingham. I was 12-yrs old, and for vacations we school kids used to go to the canneries asking for jobs, as there was no child labor law at that time. I'd be hoping the ‘China-boss’ would come out and ask, "you want work?"

The canneries in those days were the Washington Packing Co at Fairhaven, R. A. Welsh, Pacific Packing & Navigation Co (later Pacific American Fisheries), Sehome Packing Co, Astoria & Puget Sound Packing Co, at Chuckanut Bay, and one saltery belonging to Thompson Fish Co.

|

| P. A. F. Cannery |

The canning firms paid 7 to 10 cents an hour to boys piling cooled cans of salmon that had been cooked the previous day. They were wheeled out of retorts on cars that held 6 trays of tall cans, or maybe 11 to 13 trays of half-pound cans. They were cooked 90-minutes at 242-degrees, then Chinamen pulled the cans out on tracks to a warehouse, where the cans would cool overnight. The cars and trays were wanted back as soon as possible, so doors were left open to catch a breeze and cool the cans. School kids were hired to pile them as high as they could reach. The warehouse looked like a sea of cans; all night one could hear them snapping as the vacuum sealed them.

The only adult labor, around the cannery itself, was the old Chinese; they were hard-working and willing. I remember how one of them would come out from the 'China House' every morning wearing a shoulder yoke from the ends of which hung two huge cans of tea. He'd leave one of them in the warehouse for the workers. They didn't want kids standing around the pot, but we thought we should have a break also. The Chinese had a job keeping us steadily at work.

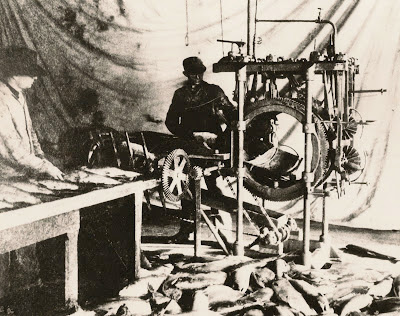

After the end of the canning season, the stacked cans were all cooled when the Chinese lacquered them with crude brown varnish thinned with naptha. This was done in the lacquering machine. The kids' job was to pick cans off the pile and lay them lengthwise on a track that slid them toward the machine. They were immersed in lacquer six or eight at a time then dumped out on conveyor chains and carried over a fan in the machine where a blast of air-dried them. The Chinese removed the cans and we kids re-stacked them to await shipping orders. Labels were applied by hand; the cans were then packed in wooden boxes that had been made at the cannery before the season opened.

Things were just beginning to be modernized and the lacquering machine was the first real improvement. Cans were still all made by hand when I got my first job in 1904. I was sent to help at the soldering bench. The Chinamen prepared their own solder in long sticks. I carried trays of side soldered can bodies to where the bottoms were soldered on. I also learned how to make complete cans from sheets of tin plate.

Around the plant were still the old vats for washing cans in lye water to remove oil after the final 90-minute cook. They were put out to dry and then the Chinese sat around and painted them red. It was explained to me that England was a great outlet for our canned salmon. When the cans were shipped through the tropics and around the Horn in sailing ships on the way to Great Britain, they would sweat and rust. If a can wasn't painted red when it got to England, it wasn't salmon. So before lacquer came in as a rust preventive, the cans were painted.

After I had worked a while at the WFA Co, the China boss took me to a pile of salmon in the fish room and told me to supply fish to the hand butchers. He gave me a picaroon and said, “you put fish on table. If table not kept full, you got no job--savvy?”

This is where I was working when Edmund Smith came from Seattle with an experimental butchering machine he wanted to try out.

Smith was the inventor of the "Iron Chink" and I sometimes ran errands for him. Because of the work, I did for him, when he perfected the machine some years later, I became contact man for the company, traveling the AK coast.

In my early years around canneries, Puget Sound fishermen used seine skiffs. They were big dories, square on one end, and could carry a crew of four to six. The men would put a tent on a beach and row out with the dory, carrying the net on the stern. To make a set they cast it off and rowed in a circle. Then they pulled in on the lead line to purse the net and brailed the fish into the boat.

About 1912, I was an engineer on the BEAVER, owned by R. A. Welsh of the Bellingham Can Co. I hadn't intended to work on a cannery tender, but the company had trouble with engineers getting drunk and asked if I wanted a job like that. I went to the Y.M.C.A. and took a gas engine course before I said yes.

|

The BEAVER She tended the first steam pile driver in San Juan county in 1894. The pile driver was owned by Kinleyside, Richardson, Lopez. Original postcard from the collection of the S. P. H. S. © |

The BEAVER had been built in Anacortes about 1894 and was 65-ft long. She had a 50-HP Troyer Fox gas engine when gas engines weren't common. I was told there were only two on the northern part of Puget Sound. We made up our batteries for ignition with sulphuric acid and carbon-zinc plates in glass jars. Welsh used the boat to pick up fish for the cannery and to take the pile-driver crew out to his traps. We would go to the San Juans and pick up fish from the little camps on the beaches. There were lots more fish in those days and they were caught most anywhere.

William Bell was captain and deckhand on the BEAVER and I was an engineer and cook. We lived on the boat. My bunk was alongside the engine and under the deck. When rain fell the deck leaked and my blankets would get wet.

Our season started about March with driving piles at West Beach and Strawberry Bay. A crew was ashore on Cypress Is at Strawberry Bay making up the web, then we towed it on a scow to where needed. In the fall we took the scow down again and picked up what was worth saving of the web. The pile puller pulled the piles and the good ones were taken to Strawberry Bay, where there used to be a dock and buildings of the main camp.

The company had two or three traps on the west coast of Whidbey Island, one at Strawberry Bay, and three in Hood Canal, at Lofall, Whiskey Spit, and Bridalbeck. I can remember going to these traps to pick up a scow load of humpback salmon then on the way back we ran into a storm and had to pull into Bowman's Bay until it was over. With only 50-HP the skipper had to work with the tides.

Mostly our runs were with a hold full of fish. We also transported men back and forth to the traps and camps.

There were no fish tickets at that time; payment to fishermen had to be in cash. The skipper went to the Fairhaven bank and got a canvas bag of bills and change, which he stowed under his pillow. He slept with a Winchester in the bunk alongside his right leg. One night when anchored in a fog I heard the skipper yelling his head off and when I got on deck he was standing at the bow shaking his fist at the fog. He had been hijacked and robbed before he could get his rifle out.

Another exciting time was when we went ashore in fog on Bird Rocks. We thought the BEAVER was going to turn over because she was at such a steep angle, so we got out and sat on the rocks, wondering what we'd do after the tide came in. However, as the water rose the boat righted, and we got back on board.

We had a peculiar experience on another occasion when we were heading out and halfway across Bellingham Bay. Suddenly I got three bells and a jingle, the signal for full speed reverse. The sudden reverse killed the old engine and when I looked out there was a periscope coming up across our bow. A sight like that gives you a queer feeling.

The explanation was simple enough. The Electric Boat Co was building two submarines for the Chilean government and picked Bellingham Bay for the trial runs. We were nearly hit by either the EQUIQUE or the ANTAFOGASTA. One of those submarines came up under a log boom in Hale's Pass; the skipper looked back and saw the logs standing on end.

Back when I began in the cannery business there was no electricity. The cannery was lit by lanterns, fish were unloaded on a platform at the dock, and pitched from there up to the cannery floor. The first fish elevator in the old plant was put in the year I went to work; its power came from the streetcar line. One of my first jobs was to sort through the fish and throw the chums overboard. It was thought their meat was too coarse and only suitable for salting. The old WPC didn't do any salting. England bought only sockeye salmon. Down on the Columbia River, the canneries saved big chinooks and packed them in oval cans. I remember the biggest king we picked up weighed 60 pounds. Anybody could have carried it home; it wasn't wanted for canning and it went to the China House.

Such were early days in the salmon canning industry on the Sound. The old BEAVER served us well. I last saw her moored among other fishing boats at Ketchikan."

Above text by Lynne McKee, as told to Lucile McDonald.

From The Sea Chest, the March 1975 quarterly journal of the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society, Seattle, WA.

No comments:

Post a Comment